The Greatest Masters

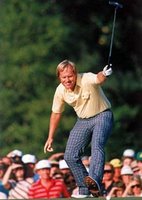

Twenty years ago this week, Jack Nicklaus arrived at Augusta for the US Masters out of form and widely regarded to be over-the-hill. Languishing 160th on the PGA Tour money list, he hadn't won a tournament in two years nor a major in six. He had missed the cut in three of the four tournaments he played that year. Yet, by Sunday, he had stormed to his sixth Masters title in the most thrilling fashion imaginable.

Twenty years ago this week, Jack Nicklaus arrived at Augusta for the US Masters out of form and widely regarded to be over-the-hill. Languishing 160th on the PGA Tour money list, he hadn't won a tournament in two years nor a major in six. He had missed the cut in three of the four tournaments he played that year. Yet, by Sunday, he had stormed to his sixth Masters title in the most thrilling fashion imaginable.One contemporary correspondent summed up the consensus on Nicklaus' chances in his pre-tournament write-up. Tom McCollister of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, in an article which was clipped and pinned to the door of the refrigerator in the house where the Nicklauses were staying, said "Nicklaus is gone, done. He just doesn't have the game anymore. It's ruined from lack of use. He's 46 and no-one that age wins the Masters."

It wasn't a sentiment which Nicklaus himself totally disagreed with. Speaking to Golf Digest magazine this month, he admitted "By 1986 I was not the player I was 15 years earlier. And I've always felt the Masters was a young man's tournament because of the speed of the greens, the firmness of the course and the demands it puts on your nerves." Still, the man regarded as the greatest golfer of them all did not want to go quietly, especially where the US Masters - arguably the greatest tournament in golf - was concerned.

The standard that year was immensely high, and in the vanguard were a group of immensely talented foreign players. After three rounds the field was led by Greg Norman on -6, followed closely by a quartet of Seve Ballesteros, Bernhard Langer, Donnie Hammond and Nick Price (who had shot a course record 63 on the Saturday, including lipping a putt for 62 on the 18th) on -5. Nicklaus lay ninth, on -2, after playing comfortably the best golf of his year in the opening rounds.

Going into the final day, he believed he would need 65 to win. It would be the score he would sign off on before collecting his sixth green jacket.

Not that it seemed that way going out. He seemed in the opening holes to be compiling a workmanlike round, missing a few putts and ending up in trees on the second and eighth - the hole which would ignite a famous charge. Hitting a three-wood out of dense trees, he wound up just short of the green, from where he made his par.

His first birdie of the day came at nine, but, at the time, it seemed academic. Ballesteros and Tom Kite had both just made eagles, leaving him five shots off the pace at the turn, despite his birdie. However, he followed it with birdies at 10 and 11, which, following a Ballesteros bogey, suddenly left him only two shots off the pace, and seemingly with all the momentum. The 12th, however, saw him tighten up and pull his tee shot at the par 3 hole. After a poor chip he was forced to take bogey and his charge seemed stalled.

For Nicklaus himself, it was the cue to get aggressive. Birdie and par were taken on 13 and 14, but Ballesteros had just made his second eagle to enjoy a two stroke lead over Kite and a four stroke lead over Nicklaus and Norman; the Spaniard looked to be cruising to the title. Not that anyone told Nicklaus: on 15 he putted from 12 feet for an eagle to move further up the jostling pack behind Ballesteros, now level with Kite on -7.

Now hitting beautifully, Nicklaus played one of his best shots of the day at the par 3 16th - a 5-iron which missed the hole by inches, allowing him to hole from 3 1/2 feet for yet another birdie. By now the noise of the crowd upon every brilliant stroke was deafening, as if being made in a roofed-over stadium, and it created a sense of building excitement which intimidated his opponents as much as it carried Nicklaus along.

Ballesteros, on the 15th, began to feel the pressure.

The Spaniard, having heard the cheers for Nicklaus on 16, took a 4-iron approach to the green - and promptly put it in the water. The magnitude of the closing holes of the Masters is substantial enough in normal times, but with the whole crowd seemingly willing their beloved Nicklaus on to an unlikely success, Ballesteros appeared to have succumbed to the atmosphere - and the cheers which accompanied his ball into the soup cannot have helped.

There was now a three way tie for the lead between Ballesteros, Nicklaus and Kite on -8, with Norman and Tom Watson on -6. Nicklaus hit a poor drive on 17, but followed with a superb shot between trees to within 12 feet. As if the concept of nerves did not exist, he rolled his putt in, to the most almighty roar of the day.

He now had the lead.

After making a good par on 18 he walked off the course to another tumultuous cheer, arm in arm with Jackie, his son and caddie - to wait. Kite and Norman were the only men who could beat him now. Kite, a shot behind, had a ten foot birdie putt on 18 to force a playoff. He underhit it and it broke left.

Norman however, had birdied 17 and was tied with Nicklaus as he stood over his approach to the 18th green. He chose a four-iron and attacked the shot. It flew into the spectators gallery, from where he chipped to 10 feet for a putt to bring the tournament to a play-off. He missed and the Golden Bear was the 1986 Masters champion, his last major, twenty-four years after his first and twenty-three after his first win at Augusta.

Jack Nicklaus played his last round at the Masters in 2005, and bowed out from professional golf in fitting style, at the Open Championship at St.Andrews last July.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home