Maracana Maravilhosa

The Cristo Redentor statue which stands atop the Corcovado mountain in Rio de Janeiro is, of course, one of the city's most instantly recognisable sights; it is as much secular brand logo for Rio as religious icon, visible as images of it are on the side of buses chugging along the Avenida Atlantica in Copacabana or on municipal billboards around the sprawling city.

The Cristo Redentor statue which stands atop the Corcovado mountain in Rio de Janeiro is, of course, one of the city's most instantly recognisable sights; it is as much secular brand logo for Rio as religious icon, visible as images of it are on the side of buses chugging along the Avenida Atlantica in Copacabana or on municipal billboards around the sprawling city.The imposing sculpture's power is derived not only from the aesthetic grandeur of its form and the audacity of its location, but also in its relationship to the city which lies beneath. Guardian, protector, proud host, the statue's slightly forward tilting head and outstretched arms seem to suggest that, while being a key part of the city's breathtaking vista, it itself is as impressed and awed by the spectacle of the Cidade Maravilhosa as the tourists that teem around its feet.

The impression on its face seems to be suggesting: "Not bad, eh?"

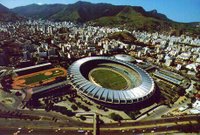

This city of superlative spectacle - the carneval, the Sugarloaf mountain, the sweep of the south city beaches of Copacabana and Ipanema, the Corcovado itself - also boasts one of football's most famous edifices: the Maracana stadium.

The vast and almost circular bowl which was constructed for the 1950 World Cup and into which 200,000 souls crammed to see Brazil's shocking loss in that tournament's final game no longer possesses such a mind-boggling capacity. Indeed when I visited it the stadium only held a maximum of 45,000, being in the process of renovation for the 2007 Pan-American Games, for which its capacity will approach a respectable 100,000.

The capacity on the night I visited was academic, as the Brazilian Championship game between Fluminense, one of the four big Rio teams, and Corinthians of Sao Paulo only drew around 10,000 people. A late 10pm Wednesday night kick-off and the clashing attraction of the second leg of the Copa Libertadores final (the South American equivalent of the Champions League) between two other Brazilian sides, Sao Paulo and Internacional, meant that only the core 'Flu' fans populated their end of the stadium.

Close your eyes, however, and the noise they made made them seem a multitude ten times their size.

Three separate samba ensembles kept a constant and overlapping rhythm, others were detailed to wave the gigantic flags in the club's tricolore of maroon, white and green; some released flares at moments of emotional peaks and the rest called and responded in a deep, guttural roar the many chants, songs and insults that soundtracked the game.

Due to the manageable size of the crowd we were able to sit amongst the Flu fans, rather than taking our seats with the rest of the placid tourists in the better seats along the sideline, thereby enjoying the full effect of the home supporters cacophonous output.

The game itself provided little for them to cheer. While Corinthians, last year's national champions, languished in last place in this year's campaign (the instability inherent in the MSI group's ownership of the club being one of the main reasons for their struggles), in one of his last games before leaving for West Ham, Carlos Tevez tormented the home side incessantly.

The little Argentinian's runs and touches pinned Flu back for the opening period, and he was able to get on the end of a cross to score the first while later setting up numerous chances for his team-mates in what was devilish display of forward play. One imagines Marlon Harewood may be spending quite some time on the bench this season.

Predictably, while both teams had tactical flaws - Corinthians left Tevez up front on his own after taking the lead when a limp Fluminense were there for the taking, while Flu started off with a 'no full-backs' strategy then attacked their deficit with the sharpness of feather duster - the level of technique on display was consistently impressive.

It wasn't juggly, flicking-the-ball-over-your-shoulder samba stuff - the game was played at a serious and competitive pace - but rather every player's touch was good, little shoulder-dropping dribbles occurred all over the field and one-twos and flicks generally came off.

This level of technical ability, standard throughout Brazilian football, is of course the reason why Brazil acts as a farm for producing players for the wealthier European leagues.

While Tevez and Javier Mascherano were helping Corinthians to victory against Fluminense shortly before packing their bags for London, Rafael Sobis, the Internacional star striker whose two goals in the first leg of the Libertadores final ensured their ultimate victory, was announcing that he had played his last game for the South American champions: his time had come to move to Europe. Sure enough, he completed his transfer to Real Betis shortly before the end of the recent transfer window.

While the notion of selling on the best talent is a familiar one to football supporters of every country outside of those predators who reside at the top of the game's economic food chain, the inevitability of the drain of talent from Brazil, while logically rooted in the financial imperatives of the country's relative poverty, is no less sad for it.

The all-consuming passion for Futebol in this country of 180 million people is unavoidable, and the love of the game, as it is played on the beach, the street or in the stadium means that it still must grate to see every new talent that comes along disappear towards the riches of Europe almost before their own people have had a chance to appreciate them.

Perhaps this only adds to the country's devotion to the Selecao, the national team who play in football's most fabled colours. When they line up at the Maracana it must feel to the locals like a visit from the gods, a chance to see and feel the best of the native genius of what their country does best, before it disappears on airplanes back to its distant, untouchable exile, waved off by the proud statue on the hill.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home